Gammell and His Students

Published Monday, December 11, 2000

The reputation of Robert Hale Ives Gammell has been rising of late: an exhibit of his series of imaginative paintings, The Hound of Heaven, is touring the country; his writings are more widely read and his influence noted; and the tradition that he alone carried through the middle years of this century — when there was almost no tolerance for representational painting — continues to be handed on through his students and his students' students.

Although Gammell began teaching in the 1930s, he didn't obtain serious students until the late '40s, after the publication of Twilight of Painting. Among these students were the late Bob Cummings, Richard Lack, Robert Douglas Hunter and Robert Cormier. These men have a unique perspective on the man responsible for carrying on the tradition of The Boston School.

Gammell worked in the Fenway Studios, #401, in Boston. His students were down the hall in #408. He'd arrive at 10:30 a.m. or so and, "get up on what he called his 'equalizer' because he was short, and we were by comparison relatively tall. He would look at our interpretation and always be on target with his criticisms," said Robert Douglas Hunter, who studied with Gammell from 1950 to 1955.

Hunter goes on, "At this time, and this is an important thing to realize, he (Gammell) was a nobody, a nothing, in the worldly sense of the term. And so in order to give force to his point of view he had to be as rigorous as possible. He was trying to get you to improve your eye, to see correctly, and that's all he was interested in. He didn't care what your reaction was; he wanted it better, better, better."

Richard Lack, who began studying with Gammell in 1950 and continued into the middle '50s, recalls, "I had never run into that kind of criticism. He was very direct, very frank. No hyperbole; just right to the point - which I appreciated, although I got a little irritated in the beginning because as a precocious art student you don't like to have people tell you that your work is awful."

Robert Cormier, who began his studies shortly after Lack and Hunter, noted, "He would go about it in a very professional way. He would discuss technique; he might say, 'Well, this is scratchy, your crosshatching isn't working.' Then he might make suggestions about how to crosshatch. Whatever you were doing, he would talk about that. Then he would look at the model very carefully and note differences in shape.

And he might mark on the drawing. He would correct the shape very carefully and slowly and pull it in. Gammell was very interested in the negative and positive shapes. He would say, 'Well, maybe the model has changed but I would prefer to think you were wrong.'" Meaning, Cormier explained, Gammell didn't want you chasing the model's gesture around. "He would say, 'Always have a clear idea of what you want to do.'" Lack stated that he was extremely honest in his approach to critiquing. "No theatrics involved whatsoever." The curriculum at Gammell's studio consisted of daily life work, memory drawing and the study of anatomy. The emphasis was always on drawing and shapes. He taught the sight-size method, and he emphasized seeing correctly.

"He didn't like drawing that was superficial," Robert Cormier said. "I remember he said to one student, 'That drawing is dangerously pretty.' He wanted you to get things right the first time. He'd mention that Paxton would say that 'It's the preparation that's everything. Any idiot can go back and put a pretty line over it.'"

Painting the figure came later in a student's career, and sometimes gave way entirely to drawing. Lack noted that he spent most of his last two years with Gammell studying shapes, doing pencil drawing.

Gammell was a member of the Boston Athenaeum, and Lack recalled that, "He stressed the intellectual understanding of art. He got me a library card at the Athenaeum, and I was really pushed to read. And he would constantly be querying me about it. 'Have you read R.A.M. Stevenson?' And then we'd talk about it, and he'd quiz me. So I was reading like I was at Harvard. And then he would question me, and his mind was very penetrating. He had the damnedest memory; he'd remember everything. It was a wonderful thing to keep pushing that intellectual side. If I had not had that I would not have been able to set my rudder, both in my own work and for the Atelier."

In addition, Gammell believed that painters should be steeped in culture. He made tickets available for the Boston Symphony and The Metropolitan Opera when it came to town. Students were expected to make regular use of the local museums as well, including The Boston Museum, The Fogg, and the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. He evaluated the gallery scene as "something to be avoided."

Cormier spoke of Gammell "very carefully" correcting his drawing, and Hunter declared, "You'd be sweating bullets for him, rather than for yourself. He was intense and somewhat agitated. He would put a little worrying stroke and say 'It's this way, this way,' and by the time he got through, after 10 or 15 minutes, you were exhausted for him."

Lack said, "He was always a little bit diffident about his ability to execute. He would say, 'I'm not very clever, I'm very clumsy.' He was not really dexterous. He called it 'finger dexterity' and he said 'I don't have any finger dexterity.' And I should mention that he was extremely honest in his approach to teaching. He would say, 'You know, I really can't draw very well.'"

"You have to remember that he worked with some damn good painters. Gammell said that when Paxton used to come in and sit with their little drawing group-there were four or five of them-that Paxton would critique them and make corrections and everybody would feel intimidated by somebody who was that masterful."

Cromier explained, "Gammell was open with his students and talked about himself and his own (artistic) problems. He'd tell you how hard he worked at his struggles; his difficulty in learning to see shapes; how he got rid of all his commissions around age 40 and just did memory drawing, for shape." Gammell worked on this for a long time, and had the satisfaction of knowing, as Cormier remarked, "that Paxton was telling people, 'Well, dammit, Gammell is learning how to see the shape.'"

"He would always bring me and the other students back to art history," Lack recalled. "That was one thing I didn't really appreciate at the time, but his analysis and critical judgment of painters was something he forced you to consider. He'd say, 'Now what do you think of this painting?' or, 'What do you think of Delacroix?', just constantly sharpening your critical judgment. "The main concept, the seeing part, as I kept saying while I was teaching, comes from Paxton, via Gammell," Lack stated. "Gammell was teaching in the way that Paxton painted, in the way that Paxton did it and in the way the two of them talked about it. Getting the note, and lost and found (edges), warms and cools, scumbling out an area and painting broadly-these are all things that Paxton worked for."

Paxton was crucial to Gammell's education and perhaps even to his persistence as a mature painter. Paxton died in 1941, so none of the young men studying with Gammell in the early 1950s ever met him. But his presence was palpable in Gammell's teaching. In his autobiography, Gammell writes that in his youth he avoided Paxton. He even goes so far as to say, "I had never particularly liked the man."

However, he records how one day, while walking along the waterfront in Provincetown, he ran into Paxton. Gammell was just back from Paris and they spoke of his trip, and of the Germans advancing toward the city. Gammell also remarked that he was not looking forward to going back to the Museum School in Boston. Then he writes: "His (Paxton's) parting words to me were, 'If you ever get stuck, come around and see me. I might be able to help you out.' I thanked him for the kind suggestion with the mental reservation that going to see him was about the last thing I could ever imagine myself doing in any case."

Gammell began the latter passage with the words, "In the course of that uneventful, industrious month, a seemingly insignificant incident occurred which was to have an incalculable effect on my life." But this passage would stand out without those words to flag it. Besides the obvious irony of Gammell's attitude toward Paxton at the time in light of his later relationship with the man, Gammell offers a description of the day as "…a gray September afternoon (with) whitecaps whipped up by a strong southwest wind…" Gammell does not often evoke his surroundings in his autobiography, and the fact that he does suggests that he recalled the day vividly.

Gammell did indeed one day find himself at Paxton's door. "He mentioned the fact," Cormier said of Gammell, "that friends took him aside when they heard he was going to study with Paxton and pleaded with him not to; they thought it was a terrible waste, and they tried to talk him out of it. Gammell said, 'This man's saying things I want to hear. It's something I care about.'"

"But he had to fight his way to it. It took him a while to get the courage up. He realized he was consigning himself to some kind of banishment from society." But for Gammell it was the move that would eventually lead to an unsurpassed knowledge and understanding of the art of painting, to the development of the necessary abilities to pursue his passion for imaginative painting, and to a relationship that lasted until Paxton's death in 1941.

"Paxton had the skill to draw more accurately than the others (of the Boston Painters)," said Hunter. "I mean just plain accurate. But you must not forget that even though Paxton was considered an American Impressionist-and these labels are so limiting because they only describe one aspect of a person - in all truth he was an academically trained painter." And although Paxton did little of the kind of imaginative work that Gammell later did, he did do mural decorations and was a fine designer of pictures. So he was well-equipped to guide Gammell in his pursuits.

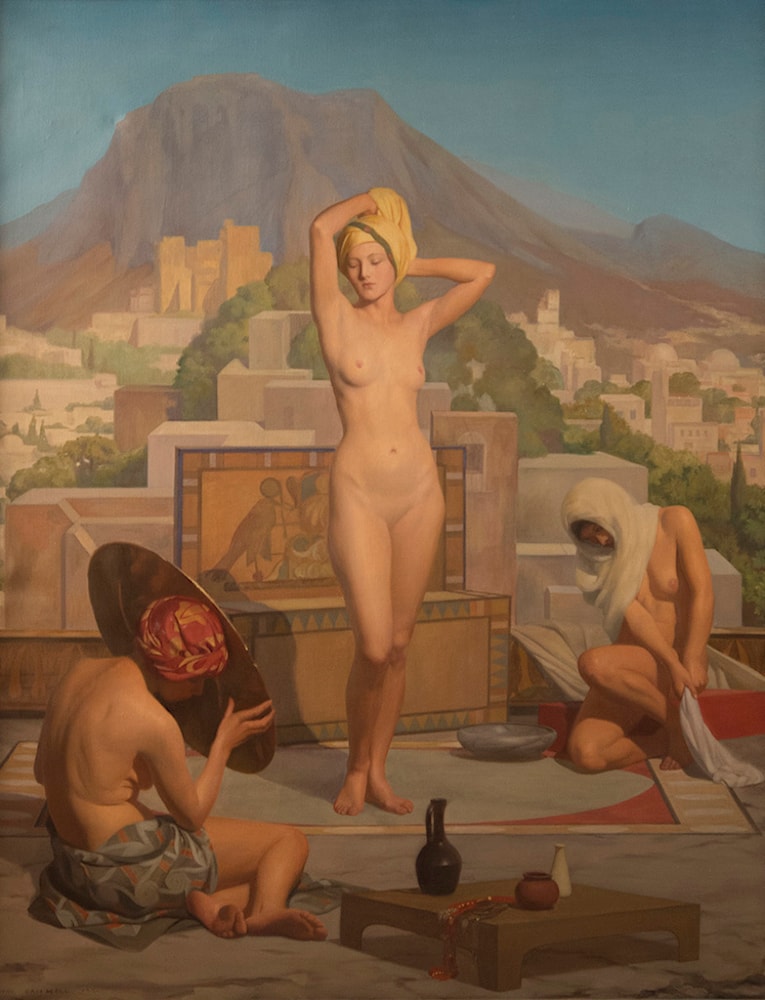

Study for Panel VI from The Hound of Heaven: A Pictorial Sequence

"He (Gammell) told me that Paxton was extraordinarily knowledgeable about painting," Lack said. "He could talk about Ingres from an understanding viewpoint, unlike most of the Impressionists, who weren't that insightful." Hunter adds that Paxton "…came in and criticized Gammell on what he was trying to do. And according to Gammell, he was always on target. Not only in the drawing, which goes without saying, but also with the designing. He had this in his background - Gérôme, Gérôme, Gérôme."

Hunter also had the following insight about Gammell's early impressions of Paxton: "Remember, when Gammell was very young he avoided Paxton like the plague because he thought he was kind of sarcastic. He got out of cast drawing at the Museum School with Paxton because he didn't want to deal with it. He didn't like Paxton, and this is very interesting."

"It's the duality of what happens with almost anybody in life. You don't take everyone hook, line and sinker. But when he returned from Paris (in 1914), he suddenly realized that Paxton knew an awful lot because now he, Gammell, knew a little bit more. Therefore he asked Paxton if he would criticize him and this continued until Paxton's death. He would have Paxton over after he had accomplished something or if he had a problem with something and ask his counsel. And according to Gammell, and you can only rely on his impression of what he got, Paxton was always on target on these definite things, because he had such a broad background in painting."

Like Lack, Hunter goes on to cite Paxton's broad interests and deep understanding of drawing and painting as important qualities that allowed him to help Gammell in his work.

There are more stories yet of Gammell's curmudgeonly, even acerbic qualities. Understandably, neither Cormier, Hunter or Lack wanted to dwell on them, but an objective picture can't be drawn without addressing this issue. "When you have a person who is that focused in a hostile art world, you are bound to have a person who has built up certain defenses over the years," Hunter pointed out. He then went on to say, "Occasionally he would be willful if he found a student he could browbeat. His technique, and it came from his Groton background, was to beat them down and get them to fight their way back up. There was no mollycoddling. It was wonderfully tough."

"To do what he did," Lack adds, "he had to be a bit of a rascal on the outside of society."

Here was general acknowledgment that some of Gammell's methods got bad results. For instance, he was known to play one student off the other, comparing accomplishments and goading students to surpass each other. He was also known to make cutting personal remarks, and on occasion to say something humiliating to one student in the presence of others. Cormier remarked that he could be "fearsome" in society and that people avoided him for that reason. That is, he would say exactly what he thought and not care who heard him. "He had a cutting voice. His words could ricochet off the walls," Cormier said, but quickly pointed out, "Anyone who does anything that lasts has strength - a strong personality - and you can't have an effect on people without sometimes rubbing them the wrong way. The worst thing you can say about a man is that he doesn't have any enemies."

There is no doubt that Gammell was independent and strong willed. "I've never met anyone in my life who had stronger will power," Lack asserted, and he believed that much of Gammell's ability to persist in the face of adversity was due to that. Lack and Hunter also cited his education at Groton, where "the people who expected to rule the country" were quartered as youngsters. (Gammell was friends with both Sumner Welles and Dean Acheson.)

It is well known that Gammell was independently wealthy, and in the opinions of Cormier, Hunter and Lack, it was his upbringing, even more than the wealth itself, which contributed to his ability to persevere. Not only were there the deeply-ingrained values of obligation and responsibility, there was the direct contact with pre-World War I culture, as Hunter pointed out. "There is therefore a store of experience that I've had which is not comparable for anyone, of any class, in today's world." "The world has changed and has become infinitely more accessible on the one hand, and more commonplace on the other." Lack added, "He was absolutely fearless in terms of his attachments; what he liked and what he didn't like. He was extremely knowledgeable and much more radical than anybody I'd ever met. He was like the invulnerable English aristocrat who wouldn't bow to anybody. He knew what he liked and he could tell you why."

On the other hand, Gammell suffered from some insecurities, artistic and personal, that caused some of the problems in his studio. Because he was unknown, he felt compelled to exert strict authority in his teaching style, and sometimes he went "a little overboard." And because he was wealthy, his artistic endeavors were not taken seriously. When he was young, some of the older painters did not think much of him; they regarded him as a rich kid playing at art. And Gammell did not always help himself in this regard. He once showed up at Paxton's door for a landscape painting excursion with a manservant along to carry his gear. Paxton reportedly told him to go away until he could carry his own gear.

In later years, when he had some real accomplishments to his credit, he still found little acceptance within the cultural milieu. "I think people sometimes actually ridiculed him," Lack remarked. "Remember, modern art was everywhere and they thought he was a very funny person to be doing what he was doing. His art was difficult anyway. So he was dismissed as both wealthy and esoteric." "I'm probably one of the few students with whom he didn't have a really loathsome argument when I retired from the student years," Robert Hunter remarked. "He didn't like his chickens to leave the nest." Of his own departure Lack said, "We had a falling out. No one could leave Gammell without a big fight." But for Hunter and Lack at least, a happier relationship lay ahead. Hunter maintained a close relationship with Gammell until his death. He became his "younger colleague" and assisted him in procuring students (Hunter taught at Vesper George). "The day before he died, I had organized a show at The St. Botolph Club, which was right next to where he lived. He came over, enjoyed Arthur Spears' work and had a great time talking with a bunch of his old cronies. Then he went home and died. So yes, I knew him, until the day before he died."

Lack spoke of Gammell's generosity. "We went down to New York to see a wonderful production of Parsifal. We had a fancy dinner at the Roosevelt Hotel. It was a whole world of wealth that opened up to me. From the standpoint of a kid coming from the Midwest, it was fun to see."

Over the years Lack maintained an ongoing correspondence with his teacher.

Hunter offered a definition of talent being the "God-given ability to do something without knowing how." Furthermore, he said that Gammell claimed to have as little talent as anyone he knew. "And that's why he did not rely upon talent," Hunter said. "His eyes were awfully good, he'd almost always be right on the ball. He didn't make mistakes. He cared terribly; he really wanted to do his job as a teacher. He said what his job was, and he did it." It is interesting to note how the men interviewed for this article met Gammell, since he was not widely known or appreciated.

As a boy, Robert Cormier attended classes in the Fenway, and as a matter of course would see Gammell, sometimes even having conversations with him in the elevator. As he got older, he recalls seeing Robert Hunter and Richard Lack coming and going. Cormier says that about age 18 or 19 he began to think seriously about studying with Gammell.

As a young man Robert Hunter was studying with Henry Hensche at the Cape School when he met Gammell by modeling for him ("we all needed bread," he recalled). He soon realized that, "This little guy with the high voice and the local reputation for being eccentric worked hard, and that was more than I could say for any other painter in that setting."

"Remember, modern art was everywhere and they thought he was a very funny person to be doing what he was doing."

Richard Lack was doing a copy of a Velasquez at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, thus making himself conspicuous, when Bob Cummings, at that time Gammell's only student, happened by. With Cummings' help he made contact with Gammell, who first discouraged him, saying he wasn't taking on students. He later consented to see him shortly after the New Year in 1950. After seeing some of Lack's drawings, Gammell invited him to hang around for a few days. Lack said he would need to go back to Minneapolis and raise some money. Gammell offered him a wage to stay and help on some decorations, qualifying it with a gruff "I don't know if you're going to be able to do this." "Well," Lack replied, "I think I can."

Two days later Gammell came into the studio as Lack worked on some tracings and, after standing behind him and watching for a few minutes, said, "Well, you'll do."

Excerpt from Gammell and his Students, by Peter Bougie, Vol. II, Issue 2, Copyright 1995 by the Classical Realism Journal. Reproduced courtesy of the Classical Realism Journal and the American Society of Classical Realism.

A Student's Recollections

by Allan Banks

These pictures were taken of Mr. Gammell in 1976 at his private studio in Williamstown, MA. The photo showing Gammell standing was taken while he was working on a student's work in pastel. He was known for giving a very thorough and hands-on approach to teaching students their craft.

The other photo of him seated in the rocker was also characteristic of his working on an imaginative piece.

Please note the yellow gloves, which he wore consistently whenever using oil paint as the turpentine had an adverse effect upon his skin. As Gammell worked, he occasionally experienced shaking of the hands, which he referred to as the "wobbles." He would wait until they subsided, then he would very deftly lay on the appropriate stroke to the canvas as only a master would.

He was 82 years old in these photos. It was on a hot, 82-degree day on a mountain hilltop that Gammell explained to me and one other student how to paint a landscape. He worked for over two hours without stopping and explained thoroughly what we were looking at and how to record it. I was always amazed at this stamina at such an advanced age.

Allan Banks is the President of the American Society of Classical Realism.

Further Reading

-

A Clarion Call for Daylight in Picture Galleries

by Kirk Richards

-

Lost Ives Gammell Letter Found

by Fred Ross

-

Classical Realism

by Stephen Gjertson

-

Tribute to Richard F. Lack

by Stephen Gjertson

-

Paul DeLorenzo

by Peter Bougie