Michelangelo

The Poetry and the Man

Michelangelo , though best known for his sculpture, was also a poet. This poetry allows us not only to explore the connection between poetry and the visual arts as a form of self expression, but also Michelangelo as a man. There are so many legends surrounding Michelangelo's motivations and actions that it is very difficult to what is true and what is simply propaganda or intrigue. There is no way to decipher what is true and what is false, with out knowing Michelangelo as a Man. The best way to do this is by looking at his work. Just as a person may learn who an author was through his writings, we can learn who Michelangelo was through his poetry and visual representations. This essay will be a concise discussion of the connection between poetry and the visual arts as a form of self expression, and what Michelangelo's self expression can tell us about Michelangelo as a man.

Before I begin to discuss Michelangelo's poetry and personality, there are a few facts the reader must know about both Michelangelo's life and poetry. Firstly, the poetry itself is filled with ellipsis and inverted word order and can be very hard to understand without a great deal of rereading and thought. As Christopher Ryan says in the introduction to his book, The Poems, "The words of Michelangelo's poetry often do not so much carry us along in their flow as stand firmly before us, waiting for our eyes to focus more finely so that the figure or figures may emerge gradually from the solid block."1 In addition to this, the poems were written in Michelangelo's own tongue, and not in English, so the beauty and certainly some of the subtly of meaning has been lost in the translation. Because of this it will be necessary to go through and explain areas of the poetry that are not clear.

In addition, the reader should know that Michelangelo was known to have been madly in love with one of his young models, Tommaso Cavalier, who he met in 1532.2

Michelangelo wrote many letters and sonnets to and for Tommaso between 1532 and 1546. James Saslow in his book Ganymede in the Renaissance describes Tommaso as being a "hansom and cultivated Roman nobleman", who Michelangelo was attracted to due to his "intelligence, exceptional physical beauty, and deep love of art and acquisitive admiration for antique sculpture."3 In addition, the reader should know that Michelangelo's relationship with Tommaso was the most deeply felt and long lasting love relationship of Michelangelo's life, Tommaso being amongst the most intimate loved ones at Michelangelo's death bed in 1564.4

One of the most influential forces for Michelangelo was his religious beliefs and his relationship with God. This is not surprising since artwork and religion have been closely related since the dawn of human life and the formation of inspiration. As George Raymond states in his book The Essentials of Aesthetics, "The products of art are to be ascribed to what is termed inspiration. When we have traced them to this overflow at the very springs of mental vitality, no one who thinks can fail to feel that, if human life anywhere can come into contact with the divine life, it must be here."5 This idea is very important, because Michelangelo very much believed that his art was a direct reflection of God, and that he could come to know God better through his art. This feeling of connection between God and the creation of art can be seen very clearly through Michelangelo's own poetry:

From ink, from pen in hand we see outflow

the several styles: high, low, and in-between;

so out of stone come noble forms or mean,

depending on how imaginative the art.

And, my dear lord, it's like that with your heart:

Humility's there in equal parts with pride.

I only see what's most like me inside

that heart of yours. As smile or grimace shows.

One who's flung seed of grief, pain, woe abroad

(rain falls, itself as pure, but changes straight

in seedbeds to rank earths variety),

He'll reap the same, by pain and sorrow gnawed.

Who eyes great beauty through a grief as great

sees only his suffering soul, racked with anxiety. 6

This poem is very important to understanding Michelangelo, because it reveals not only how he views his art in connection with God, but goes on to indicate that Michelangelo, out of all the variety of feelings and circumstances that can come into an individual life, has been burdened with a great deal of sorrow, and although he can "eye" great beauty in the world through this grief, he can only see his own "suffering soul" for which he holds God responsible.

Although Michelangelo did love his God, he also had a lot of anger towards him, most likely stemming from his internal struggle with his sexuality and his extreme poles of emotion. One can tell Michelangelo felt this way by examining another one of Michelangelo's Poems:

I wish I'd want what I don't want, Lord, at all.

Between this heart and Your fire an icy screen,

invisible, damps it down, so these routine

words falsify what I do; the pages lie.

Tongue says it loves you, but the heart's reply

is chilling: there is no love there. Nor can I know

which way to let grace enter, immerse it so

hard-hearted pride is hell bent for a fall.

You be the one, Lord! Rend it! ramming through

closure that saw Your beauty dim and dwindle,

once light of the world's one sun, now cold as stone.

Send now the promised light that's one day due

to Your comely bride on earth! Oh then I'll kindle

the fire within, doubt-free, feeling You alone.7

In this poem Michelangelo tells God that he does not love him because he is so cruel to him. This is referred to when Michelangelo says "Your fire an icy screen, damps it down", "it", referring to Michelangelo's own heart. He goes on to say that although he reads psalms from the bible he does not feel their meaning fits the way he feels towards God. We can see this when Michelangelo says "these routine words falsify what I do; the pages lie".8 He then proceeds to say that he does not love God, nor does he know how to let God's grace enter him. But, if God were to force himself into Michelangelo's heart and give him all the love and bountifulness promised to those who love and worship God, that he would love God alone. This can be seen in Michelangelo's statements towards the end of the poem. The statement "You be the one, Lord! Rend it! Ramming through closure that saw your beauty dim and dwindle", refers to the force I mentioned Michelangelo wants God to use to have grace enter him.

The "promised light" refers to the love and bountifulness God said he would give his worshipers in the afterlife, and "comely bride on earth" refers to none other then Michelangelo himself. In the phrase,

"Between this heart and your fire an icy screen, invisible, damps it down" Michelangelo points out to the reader that there are two things that are weighing heavily on his soul, the cruelty of God and his own heart. The reference to his own heart, in combination with his expressing dissatisfaction and blame on God for his troubled spirit, points towards his discomfort with his own sexuality. So when this understanding of the poem is linked together cohesively, the reader can understand that what Michelangelo means when he states, "wishes he wants, that he doesn't want at all" is a woman rather then a man like Tommaso Cavalier.

Despite this, Michelangelo did have a great deal of affection for God which can be seen in some of his other poems, as well as his religious sculptures. If one looks at the Pietá9 for example, the subtlety and care that was taken in sculpting the beautiful, loving, and yet sorrowful face of Christ, clearly points to the fact that Michelangelo truly loved God and had a very clear image of how he wanted Christ to be depicted.10 As Umberto Baldini says in The Complete Works of Michelangelo "In designing the human shape of the first non-heroic Christ he gave him an almost boyish body, as if to exalt an extreme chastity, an absolute and uncorrupted purity despite the seemingly hermaphroditic beauty."11 This is very interesting since Michelangelo viewed himself as being corrupted by his own sexual desires, which are very much linked to his own sense of manhood. To chose to depict Christ with a boyish and slightly feminine presence, Michelangelo tries to show the extreme diversity between how he views the purity he sees in Christ versus the corruption he sees in himself. Mary looks down at the boyish Christ with sadness and love. These are the same emotions that Michelangelo had towards God, his love of God's grace and the awe inspiring quality in all God's creation, yet at the same time the sadness Michelangelo felt from being detached from this state of holiness.

There's nothing lower on earth, of less account

than I feel I am, and am, Lord, without You.

What fluttering faint breath I've left must sue

for pardon from You — You height of my desire.

Lower that chain, I pray Lord, its entire

length, link by link, each strung with gifts from heaven;

faith's chain, I mean; I'd cling there and have striven,

mea culpa, in vain; grace fails; I try but can't

This gift of gifts is all the more a treasure,

for rare is precious, and rare it is. The earth,

void of it, is void of peace, void of serenity.

Giving blood, you didn't stint; gave without measure.

What good's your gift though? Wasted all its worth

unless heaven opens to this other key.12

In this poem Michelangelo professes his love for God and the agony he feels, because he believes he is unworthy and unable to receive God's grace and mercy. His love for God is plainly stated when he says "There's nothing lower on earth, of less account than I feel I am, and am, Lord, without You." It is in this phrase that he reveals not only his sense of worthlessness, but his belief that he is worthless because he is without God. Later in the poem he refers to God when he says "You height of my desire", also revealing his love for God, as well as a burning desire to be forgiven. The most telling phrases of this poem truly divulge Michelangelo's feelings of self loathing and responsibility for his separation from God. We first see this when Michelangelo says "What fluttering faint breath I've left must sue for pardon from You". Here Michelangelo is clearly asking for God's forgiveness, and then asks again when he says "faith's chain, I mean; I'd cling there and have striven, mea culpa, in vain; grace fails" admitting that it is mea culpa, his own fault, that grace has failed him. At the end of the poem, when Michelangelo says "Giving blood, you didn't stint; gave without measure. What good's your gift though? Wasted all its worth unless heaven opens to this other key.' Michelangelo is referring to the blood of Christ, and how Christ died for the sins of man. However, Michelangelo is also saying that unless God can forgive him for his lack of faith, God's sacrifice of his only son will have been wasted on him.

Although Michelangelo did have a lot of frustration and rage associated with his feelings for God, there was also an undeniable love for God and an unrelenting desire for his approval. If Michelangelo truly hated God, why would he speak to Him and about Him so frequently and with so much emotion?

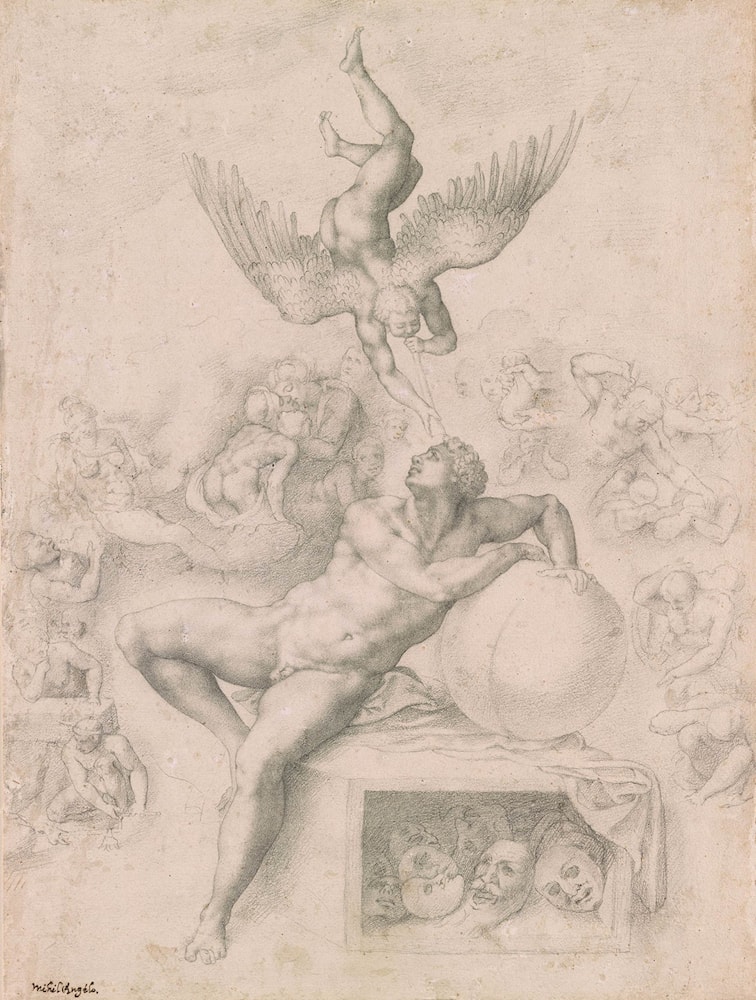

Michelangelo struggled greatly with the world around him, which can be seen most clearly in his drawing of Il Sogno, The Dream of Human Life, as well as in his poetry.13 In this drawing, the central figure appears to be falling over a box, leaning all his weight on a great sphere that looks as though it might roll off the edge, certainly causing the figure to fall. In the box are masks, images of falsehoods and facades, while the central figure himself is surrounded by figures that are fighting, thinking, eating, and making love. From the heavens, an angel descends, blowing a horn directly into the central figures face. The figure appears to be both frightened and overwhelmed.

In Maria Ruvoldt's book, The Italian Renaissance Imagery of Inspiration: Metaphors of Sex, Sleep, and Dreams she discusses The Dream of Human Life as being understood, since the seventeenth century, to be a representation of the human soul transcending from vice on earth to virtue in heaven. She also discusses how the piece embodies the idea of Divine Inspiration, and the Ficinian notion of furor, which is the irrational state between ecstasy and madness.14 It is very clear from her accompanying images that Is Sogno follows in a long tradition of such depictions. However, in Michelangelo's case I believe his decision to use this imagery was a personal one as well as universal. Ruvoldt delves into several meanings of the different elements in this piece. For example, the trumpeter has well understood artistic connections to the idea of God's act of creating the universe, as well as the symbolic meaning of calling to attention such as in recognition or Fame. Most interesting however, and most useful to my interpretation of this piece, is the belief that the trumpet is also making a reference toThe Revelations of St. John the Divine, which describes angels sounding trumpets as being the way in which God will awake the dead on the day of the Last Judgment.15 God's Judgment of Michelangelo was something that weighed very heavily on his mind. He talks about God's disapproval of him in many of his poems, and in the following poem he writes specifically about being rid of his human body and the day of his last judgment:

Rid of this nagging nattering cadaver,

dear lord, and tattered all my bonds with earth,

like one worn out, a sprung old skiff, I'd berth

back in your halcyon cove, foul weather done.

The thorns, the spikes, the wounded palms each one,

your mild and kindly all-forgiving face,

promise me full repentance, thanks to grace

rained on my somber sole — and reprieve forever.

Don't judge with justice as your holy eyes,

and your ear, as pure as dawn, review my past;

don't let your long arm, hovering, fix and harden.

Let your blood be enough to purge for Paradise

my sump of sin, and, as I age, flow fast

and faster yet with indulgence, total pardon.16

I feel that although The Dream of Human Life can be interpreted to represent Divine Inspiration, it is very likely that the piece is also a personal allegory for Michelangelo of his own existence. Michelangelo was very uncomfortable with his sexuality, and viewed himself to be unable to resist human vice, which fits into the traditional interpretation of the figure looking to heaven to be pulled out of vice into virtue. However, in Michelangelo's case, Michelangelo did not believe he could find virtue in himself, which explains why the central figure appears to be frightened and overwhelmed. The figure, Michelangelo, is being attacked from all sides. Not only from the world around him, but also by God Himself who he worships so much, and so desperately wants approval from. The iconography of birds in flight was important to Michelangelo and is symbolic of Michelangelo's sexuality. He depicts them not only in his drawings, but talks about them frequently in his poems. Although he was attracted to Tommaso Cavalier he felt it was wrong to feel this way in the eyes of God. His internal struggle can be seen in both his depiction of Ganymede and The Punishment of Tityos, as well as in his poetry. The following is a sonnet by Michelangelo, written for Tommaso late in the year 1532:

If the hope that you give me is true, if the great desire, that has

been granted me is true, let the wall raise up between these two

be broken down, for hidden difficulties have a double force.

If in you, my dear lord, I love only what you most love in

yourself, do not be disdainful, for it is simply one spirit loving the other.

What I long for and discover in your lovely face, and what is

badly understood by human minds — whoever would know this

must first die. 17

In this poem he talks about his desire for Tommaso and asks God not to be disdainful of him because his desire for Tommaso is only an act of one soul loving another. He goes on to say that he hopes to discover in God's face that his homosexual feelings are not sinful, but to know this for sure he will have to wait until he dies.

We can see how these conflicting feelings are expressed in his drawings of Ganymede and The Punishment of Tityos, both which were given as gifts to Tommaso Cavalier in 153318. Along with the drawings, Michelangelo enclosed a letter to Tommaso. He made two drafts of this letter before sending the final version to Tommaso. The most interesting aspect to be found in the comparison of the two drafts is that a suggestive postscript was removed from the final letter which read "it would be permissible to name to the one receiving this, the things that a man gives, but out of nicety it will not be done here."19 This is very telling, because although the drawings appear to be sexual, the fact that he gave them to Tommaso, and then drafted a letter with a suggestive phrase (which was then removed in the second version) reassures us and give great credence to this assumption.

Before going into an analysis of the Ganymede and Tityos drawings, it is important that the reader understands that both these subject matters come out of Greek mythology and are depicted often throughout the Renaissance; but not with the same unique interpretation that Michelangelo gives to them. In the legend of Ganymede, Ganymede was a mortal man who was so beautiful he captured the heart of Zeus. As the legend goes, Zeus transformed himself into an eagle and carried the young man off to Olympus to have his way with him. This legend, which has a mortal man as a hero who has the power to sexually arouse the most important male god of Greek mythology, is the perfect subject material and context for Michelangelo to use in order to express his homosexual desires. Similarly, the story of Tityos has sexual connotations connected to it, although they are not specifically homosexual. In the Story of Tityos, Tityos was punished for trying to rape Leto, Apollo's mother. His punishment was to be bound to a rock where two vultures would continually eat him alive. This story came to be understood very early on in history to be an illustration for the punishment of unwelcome and unsuccessful seduction. 20

The two drawings can be seen to represent the two different sides to Michelangelo's sexuality. The first drawing of Ganymede21 represents his desire and lust, and the second drawing of Tityos22 represents his shame, discomfort, and fear. As Rona Goffen says in her article titled "Renaissance Dreams": "For Michelangelo, he not only said more in his drawings, he said it more directly then he dared in his letters and sonnets." Goffen continues in her article to discuss how the tail feathers of the bird in the Ganymede drawing are raised, very directly, informing the viewer that the two figures are doing more then just flying. Goffen says, "This is not merely a literal flight to heaven, like previous Renaissance depictions of the subject, but a figurative transportation to ecstasy, and the expression on Ganymede's face reveals his pleasure in the act — not fear caused by his air-born rape, not anticipation of love, but its climax." Goffen interprets the Tityos drawing to be an allegory of Michelangelo. Rather then the young boy Ganymede, Tityos is more muscular and more mature, and the vulture sent by the gods to torture him can be interpreted to be none other then Tommaso Cavalieri.

In addition to this interpretation, I believe that the drawings, rather then being directly representative of, in Ganymede, Michelangelo being the bird and Tommaso being the boy, and in Tityos, Tommaso being the bird and Michelangelo the man; that both drawings are simply allegorical representations of Michelangelo fulfilling his sexual desires. The legends allow Michelangelo full and safe expression of his desires, rather than the repression of them because they are wrong in the eyes of God. The bird appears to be the same bird in both drawings, and both Ganymede and Tityos are depicted as being muscular and attractive men. The only real difference when one looks objectively at the two drawings is that in Ganymede, the figure is submitting to the bird's will and is enjoying it, and in Tityos, the figure is desperately fighting with the bird, and is clearly trying to resist without success. Considering that Michelangelo speaks often in his poetry of how he wishes he could control his desires, (for example in the poem already used above "I wish I'd want what I don't want, Lord, at all"), it makes perfect sense that in a drawing that expresses these feelings, he would represent himself as fighting with his lust. Also, Michelangelo referred to love as being like a phoenix, a similar bird of pray, in several of his poems.

If I had believed that at the first sight of this dear phoenix in

the hot sun I should renew myself through fire, as does that bird

in its extreme old age, a fire in which my whole being burns,

then as the swiftest deer or lynx or leopard seeks its good and

flees what does it harm, I should before this have run to his

actions, smile and virtuous words, where now I am eager but slow.

But why go on lamenting, since I see in the eyes of this happy

angel alone my peace, my rest and salvation?

Perhaps it would have been for the worse to have seen and

heard him before, if he now gives me wings like his for me to fly with

him, following where his virtue leads.23

This poem, written for Tommaso just a few months before the gift of the pictures, refers to the phoenix as constantly renewing itself through "a fire in which my whole being burns". In my interpretation, the fire and the phoenix are allegorical of the cycle of love. The angel he refers to is Tommaso who has the power to give him wings to fly. But the wings he refers to are the wings of love. This is in opposition to the wings of God. We can see this when Michelangelo says he will follow Tommaso where "his virtue leads". This is very interesting when one looks back on the meaning of his Dream of Human Life in which God is pulling Michelangelo out of vice into virtue. Here, in this piece, Michelangelo is allowing himself to be pulled into vice and saying it is up to Tommaso's virtue to lead him, not the virtue of God. This only further affirms the two sides of Michelangelo's deep conflicted soul. In Michelangelo's the Dying Slave, originally sculpted for the tomb of Julius II, we see in stone the same theme of bondage that Michelangelo often talked of in his poetry.24

Why ease the tension of this wild desire

with tears and sighing and words woebegone,

if this heavy cloak of grief the heavens have drawn

around us all, won't loosen soon or late?

Why does the heart urge "Languish on" if fate

shows death ahead for all? So let my eyes

conclude their days in peace. No earthly prize

seduces like love's agonizing fire.

But if the blow I sought myself, by sleight,

falls so I can't escape, my fate foreknown,

who's there, between grief and sweetness, meant for me?

If being bested and bound is my delight,

no wonder I'm made a prisoner, nude, alone,

as a cavalier in armor turns the key.25

Here Michelangelo fully describes what The Dying Slave embodies. He is a prisoner, nude, and alone. The look on The Dying Slave's face 26 appears to lie somewhere between grief and sweetness. A slight discomfort can be seen in the face, while the body is highly eroticized. The way the figure is rubbing his legs together, touching his chest, and has his head tilting backward, all make the figure look as though he is in a state of ecstasy, although the viewer knows otherwise, that sculpture is titled The Dying Slave. We know that the figure is in fact dying. This is just as Michelangelo felt when he wrote the above poem. He further discusses how he is a slave to love in the following poem:

When with a clanking chain a master locks

in jail a slave with no amnesty, no hope,

the victim slumps and submits to it, will cope

with oppression rather than fussing to go free.

So tiger and snake suffer captivity,

And the lion, rampageous, in rank jungles born.

So too the young artist, harried, worry-worn,

learns to endure from bearing with hard knocks.

Only the fire of passion shuns compliance:

though it may leave green sapwood sere and dry,

in an old man's cooling heart it stays aglow;

alluring him back to young love's wild defiance,

it renews, ignites, enraptures, kindles high

both heart and sole with the breath of love...27

Both of these poems refer to the ideas of slavery and bondage in connection with love. The Dying Slave very much fits into this category as well. Although Michelangelo may not have consciously created The Dying Slave with the suffering of his own soul in mind, his internal struggle was so great that it had to have had an influence on this piece, if not consciously, then subconsciously.

Michelangelo is one of, if not the most well known sculptor in the western world, though very few understand who Michelangelo was as a man. Through his poetry, one can see that Michelangelo talked very little of his work as an artist, and very often of the two things in his life that caused him the most joy and sorrow. Those two thing being God and love, probably the two most elusive forces in any human being's life. But for Michelangelo, the two most important elements of his existence were in constant conflict. He did not believe it was possible for him to love another man and God at the same time, since he believed that the way he loved was wrong in God's eyes. When understanding this relentless conflict and torment under which Michelangelo lived and worked one can view and empathize with Michelangelo, the man, more clearly and see him as he really was, one of the truly tragic figures of history; because despite all his genius, fame and success, it would be hard to say that he was ever truly happy.

-large.jpg?w=200)