Obituary of Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema

(The Times, 26th June 1912)

Obituary

We record with much regret that Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema , OM, RA, died at Wiesbaden at 1.30 yesterday morning without regaining consciousness. His daughters were present at his death. Sir Lawrence had been undergoing treatment at Wiesbaden for about three weeks. Ten days ago his condition became worse, but the doctors could not risk an operation. The body will be brought to England, leaving Wiesbaden tomorrow.

Laurens Alma Tadema — who after his settlement in England changed the spelling of his first Christian name and joined the second to his surname - was the son of Peter Tadema, a notary of Leeuwarden, and was born at the neighbouring village of Donryp on January 8 1836. His father died when the boy was but four years old, and he was brought up entirely by his mother, a woman of energy and courage, who made a brave struggle in the face of adverse circumstances. The history of his boyhood is that of many artists. He very early showed a talent for drawing and longed to be a painter; but his mother and his guardians wished him to follow his father's profession, the very idea of which he hated. There was something of a struggle, and the authorities did not yield until a nervous illness convinced them that the boy's obvious natural bent must be followed and that he must be allowed to become an artist. It is said that he was refused as a student by various Academies in Holland, but he was fortunate enough to find an opening, where, in the Academy of Art, he began his studies under Wappers , the leader of a kind of national reaction against the pseudo-classical ideals and methods adopted by the followers of J. L. David . Under this congenial teaching the hard-working youth of 20 made rapid progress; but it was nothing to the strides which he took under his next master, the celebrated Baron Leys , whose memory to the end of his life he always preserved with affection, and whose influence, as he at all times admitted was of immense value to his art.

Young Tadema assisted Leys in painting the frescos for the Antwerp Town Hall; he assimilated the master's method of method of using his colours he followed him in that precise attention to architectural and other detail which was the special mark of the school, and above all he was encouraged by Leys in that preference for antiquarian subjects which remained characteristic of him to the end. Leys was a Belgian patriot, deeply interested in the history of his country, especially during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, and Tadema followed him in his first researches which were into the history of those semi-barbarous Germanic tribes which overran France and the Netherlands at the break up of the Roman Empire. The earliest of his pictures which remained famous are two illustrating this period, subjects of which may be derived from the pages of the old historian Gregory of Tours. The first (1858), was Clotilde at the tomb of her grandchildren, and the second was The education of the children of Clovis, which was exhibited at Antwerp in 1861, when the painter was 25; a brilliant work more or less in the manner of Leys, but promising by, it's animation and its great sense of individual character, an artistic eminence to which Leys never attained. These were the first of a series Merovingian pictures, the best of which was Fredegonde at the Death of Praetextatus, illustrating once again the young painter's power of selecting really picturesque from the old chronicles, and sharply defining the character of his personages, and of lavishing upon his work a wealth of costly and decorative detail. It is interesting, for example, to note that on the pavement in the Fredegonde, picture is a magnificent Roman mosaic, though the painter had not yet turned his special attention to the Roman splendours which he was destined to paint in hundreds of subsequent pictures.

For some ten years he was faithful to the Merovingians, but in 1863 having gone back many centuries for his inspiration, he produced the well-remembered picture Egyptians Three Thousand Years Ago. Egypt satisfied him for two or three years, and formed the subject of perhaps a dozen pictures: but about the year 1865 he turned definitely to Rome and to the Imperial civilisation which was to satisfy him for the rest of his life. Pictures like The Honeymoon, Lesbia, and, above all Tarquinius Superbus, were naturally greeted not only as marking a new stage in the young painter's career, but as revealing a talent even greater than that of Gerome himself for illustrating Roman life in a manner that pleased even scholars, and awoke something like enthusiasm in the cultivated public. A few sceptics may doubt whether the Romans and their surroundings were really like this, but at least the representations were immensely plausible, and there was no doubt about the impressiveness of young Tarquin, any more than there was about the beauty of the bed of poppies before which he stood. Henceforth Tadema had found his milieu, and he went on from strength to strength, sending forth from his easel every year some four or five pictures which charmed a rapidly-increasing public, and each one of which was, in what painters call quality, an improvement of the one before. Its enough to mention three painted towards the end of the sixties to show what pitch of excellence Tadema had arrived at before his 35th year. These are A Roman Amateur, (1868), The Convalescent, (1868), and The Phyrric Dance, (1869). Many people still remember the impression made when the last-named picture, the work of a foreign artist little known in England, was exhibited at the Royal Academy in the year of its production, and how everybody admired the spirit, the energy, the movement of those dancing warriors, with their raised shields, and the expressions of blasé indifference in the faces of the spectators. It was evident that a young painter who could do work like this was on the high road to a great position.

Obituary: Settlement in England

In that same year Tadema came to live in England. He originally came to England to consult the famous surgeon Sir Henry Thomson, who used his influence to persuade his patient and friend to remain here. Tadema had just lost his first wife, who had been a Mlle de Gressin de Bois Girard, and whom he had married six years before and taken to live in Brussels. It was after her death that he migrated to London with his two little daughters, the elder of whom is now well-known as a writer and the other as a painter who far too seldom exhibits water-colour drawings of rare quality. Two years later, having definitely made his home in England, Tadema married Miss Laura Epps , who subsequently became an artist of great distinction, and whose face, appearing in many of her husband's pictures, was well-known to thousands, while she herself, the most gracious of hostesses, was loved by innumerable friends. It was only three years ago that her death caused general mourning throughout this wide circle.

To dwell for a moment on their home life, we may here say that the Tademas lived first at Townshend House, facing the north side of Regent's Park, and that for several years this ordinary London dwelling-transformed by the artist's taste into a sort of miniature palace of the Imperial time was the centre of a delightful hospitality. Some years later a tragic event happened; a barge laden with gunpowder exploded on the Regent's Park Canal, and Townshend House was almost ruined. Tadema never cared to go back to it; but, nothing daunted, he took the French artist Tissot's much larger house in Grove End Road, and after two or three years prodigious labour, during which he spent a large part of the fortune which his paintings had by this time brought him, he transformed this also into one of the most wonderful abodes which any artist since Rubens has ever inhabited. An authorized account of this building stated long ago It is its creator's purpose that this residence shall be essentially a workers house. There are to be no superfluous rooms such as drawing rooms or fancy apartments. All there is to be of use. And so it was, since the main rooms were three studios; but assuredly never was use more carefully combined with beauty and with exquisite detail. More need not be said, since the many surviving friends who in happier days gathered in that studio to hear Joachim, or Sarasate or Paderewski, or some of the great singers of our time, and who in the intervals would stand to admire the master's easel to admire some half-finished picture, scarcely need to be reminded of the marvelous finish of the building.

In the winter of 1882, when Tadema was only 46, his pictures were already numerous enough to form an exhibition which filled the three rooms of The Grosvenor Gallery. He had followed from the early days the practice of the great musicians in numbering his works, and the latest of those exhibited at this time bore the mark Op 242. In the 30 busy years that followed that number must have more than doubled, so that the total if we remember that every one of these pictures, large or small, is a work carried to the highest point of finish of which the artist was capable is truly astonishing. Many portrait painters like Romney and Reynolds , have during a long career produced perhaps a couple of thousand portraits; but a portrait if one has the talent of a Romney, is a matter of three or four days work. The case is very different with a picture so elaborate in every detail as even the smallest detail of Tadema's performances; a picture in which an error of a quarter of an inch , not only in a face or a principle figure, but the humblest of accessories, may make all the difference. In point of fact Tadema combined with his other and greater gifts a patience, a conscientiousness, an accuracy of eye, and a facility of hand that were extraordinary and perhaps unique. The world has seen greater artists than he was, if we are to measure greatness by their success in interpreting the higher ideas of their time; but assuredly none even of Tadema's Dutch predecessors of the 17th century ever surpassed him in the gifts that we have mentioned, or ever painted 500 pictures with which, given the artistic assumptions on which they were based, so few faults could be found.

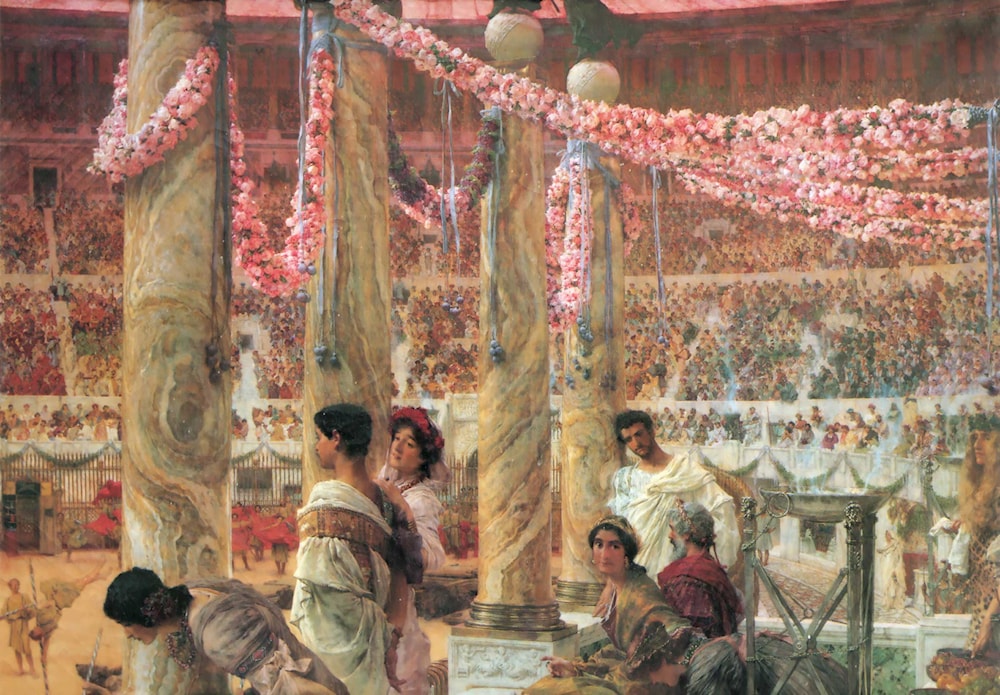

Those who have found his art unsatisfactory, as many have done, base their objections on another assumption, namely, that attempts to reconstruct a bygone society, bygone life, and bygone ideas, are foredoomed to failure, and that however perfectly Tadema may have painted A Roman Sculpture Gallery , or such marvels as the comparatively recent pictures as The Roses of Heliogabalus, and Geta and Caracella, the result is a mere archaeological exercise not worthy of the pains spent upon it. The answer is that Tadema could do those things, did them, and enjoyed doing them: that in their performance he achieved something that nobody else has achieved quite so perfectly; and that the painted result of his labours has for half a century given pleasure to an immense number of people of all countries who are neither stupid or uneducated. Moreover if the critics are bored by the number of these Greco-Roman illustrations, they must be reminded that it is only by working pretty assiduously within a limited field that anybody can arrive at perfection. One of the most astonishing things about Alma-Tadema's art is that the oftener he painted marble and roses the better he painted them. Or at least if he reached his highest point twenty years ago in the exquisite little picture called The Apodyterium, many of the later pictures, such as the two famous examples just mentioned, show no decline in the matter of detail. The very last thing to say of his work is that it is in any sense mechanical. We may almost indulge in a paradox, and say that though he always painted subjects that were more or less alike, he never quite repeated himself. Though no painting could be less like scene-painting than his, the stage was glad to make use of his knowledge. As early as 1880 he was at work on the production of Coriolanus which Sir Henry Irving only exhibited in 1901. For the Lyceum Theatre he designed also the production of Cymbeline in 1896, and his work has been seen at other London theatres.

Alma-Tadema became a naturalized Englishman soon after he took up residence in England. He was elected ARA in 1874, and RA in 1879, he was also a member of the Royal Watercolour Society, to whose exhibitions he contributed many exquisite drawings. He was knighted in 1899 and received the Order of Merit in 1905. He worked to the end with unflagging zeal; witness his important pictures in the present Academy Exhibition. He was of a genial and kindly nature, always ready to help the struggling and fallen, a hard worker on the Council of the Royal Academy, and on bodies like the Artists General Benevolent Institution. He was personally popular amongst his brethren at home and abroad, and his reception at the public dinner given during the Vandyek Exhibition in Antwerp in was a such as none of those who were present are likely to forget.

Comments on the Obituary (Vern Grosvenor Swanson)

his obituary confirms and clarifies many facts about Alma-Tadema, his character and career. He was extraordinarily ambitious, calculating, and focussed on achieving success. As a widower with two small children, he did not hesitate to leave his home country and move to England when he saw it to be in his interest to do so. The creation of his second home at Grove End Road was an expensive exercise in self-promotion a costly gamble which paid off handsomely. Alma-Tadema's musical at homes became a feature of the London social scene, with invitations eagerly sought after. The Prince of Wales attended these parties as did Lord Leighton . The performers included Joseph Joachim, widely held to be the greatest violinist in the world, in the second half of the nineteenth century. Sarasate another virtuoso violinist, and Ignace Paderwski the celebrated pianist who ultimately became President of Poland, and whose portrait Alma-Tadema painted. It is worth noting that the artist could have been one of the great portrait painters of his day had he so wished. What a showpiece these at homes were for new pictures, to the distinguished and wealthy guests.

Following the death of Alma-Tadema his beautiful home was destroyed without a second thought by ignorant greedy people, as the cultured establishment of the day sat by and allowed them to do it. What a tragedy and what an asset it would be today.

Alma-Tadema must have been a most likeable individual. He was well-known, and much loved for his boisterousness, and his sense of humour. His obvious ambition and drive had no effect on his personal popularity. With Millais he was one of the great painter-entrepreneurs of the second half of the nineteenth century.

Alma Tadema Contemporary Comment from Pall Mall Gazette Extra no 62: The Pictures of 1892 and the Men Who Paint Them.

Mr Tadema has three pictures in the Academy this year, and two in the New Gallery — "a fair division," as he smilingly remarked to a visitor who called at his studio. Two portraits and a picture are at Burlington House; one portrait and a picture at the New Gallery.

The Academy picture is called "A Kiss". It represents a marble terrace upon the shores of a lake, with steps that lead down to the water. Bathers are ascending and descending the steps, lounging on the terrace, and disporting themselves in the water. Prominent among them is a little girl standing with her mother on the terrace; and she it is who receives from one of the lady bathers the kiss which gives the work its title. "The picture was suggested to me by a view from Professor Ebers's house in the Tyrol;" and there, no doubt, the necessary studies for it were made. Mr Tadema's portrait of Mr Alfred Waterhouse RA, is at the Academy. The other Academy portrait represents the Archdeacon of Durham.

The little picture which Mr Tadema has sent to the New Gallery has been painted for Mr Tate, who, if we remember rightly, does not at present possess any example of this artist's work. It was suggested by some lines from Goethe's poems. A lover-presumably a Roman centurion-brings a bunch of flowers to his beloved. It is a warm summer afternoon, and, finding her fast asleep, he leaves the pink rosebuds in her lap, doubting not that the evening greeting will be all the sweeter for the present which he has so made. Portrait of Ignacy Jan Paderewski — "as he sat playing my piano" — with a striking background is also at the New Gallery.

A representative who visited Mr Tadema in his studio writes: "As we stood in a small gallery looking down upon a Pompeian bath-room, I asked him how it was that he had so mavelously caught the glitening aspect of white marble which is so striking a feature in his classic pictures and he replied "I was in Ghent in 1858, in a big marble room, and I was much struck by the transparency of marble. It fascinated me. And yet I always paint it from memory, never from the thing itself, otherwise I should give it too many veins."

Passing into the studio, I found myself in a large and lofty room with a high vaulted ceiling, around one side of which ran a gallery leading to a charming little room overlooking the palms and ferns in the glasshouse beneath, and which was exquisitely adorned with Mr Tadema's pictures. I asked him if he "read up his pictures". "No," replied he, "I have read up but little, but I have always been possessed of the beauty of antiquity. I have, of course, a certain amount of archeological knowledge, and I am very careful about details; where my success comes in most specaially is in my attempts to make the pictures living. I throw myself in to the past as far as I am able. That is where Rider Haggard has succeeded: he has feeling, although he may not be scientifically exact. No, I have never been in Egypt, and I dread to go there. I should only be able to see the Turks and the Arabs of today, and my soul would be swallowed up by them. And yet I should realize all the mystery and the beauty or its antiquity if I could find myself alone in the ruins of Carnac or of Thebes."

Acknowledgement

Our thanks go to Paul Ripley for kindly allowing us to quote these articles from his website, Victorian Art in Britain.