Re-entering the Canon: Giovanni Battista Moroni

Published on Sunday, January 7, 2018

There are some 26 paintings by the great 16th Century painter Giovanni Battista Moroni in American museums, scattered across the country from coast to coast. Additionally there's one in Honolulu, and yet another in Ottawa, Canada. These works can be found in the most august institutions.1 Three are in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (one is eternally in storage) and three in the National Gallery, Washington DC. Despite availability and even ubiquity, Moroni is not a name one hears often in America. Many fairly knowledgeable people have hardly heard of him at all. 1

Works by Moroni are found in the Cleveland Museum, The De Young Museum, San Francisco, Isabella Stewart Gardner and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, VA. Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Princeton Art Museum, Detroit Institute, Brooks Museum of Art, Memphis, Minneapolis Museum of Art, Ringling Museum, Sarasota. There are several attributed works in other museums, as well as at least one portrait in private hands.

This is not true in England. The National Gallery in London has the second largest collection (all eleven on display) of Moroni's paintings in the world. Recently, the Royal Academy of Arts saw fit to honor Moroni with an exhibition from October 25, 2014 to January 25, 2015 that received major critical and popular coverage, making fans practically overnight.

In Bergamo, Moroni has always been celebrated as a native son although he lived and painted most of his career in the far smaller town of Albino. His portraits have a dedicated room in Bergamo's Accademia Carrara. In Lombardy, Moroni has been treated as a superstar in the art historical firmament with large-scale monographic exhibitions, and smaller focus exhibitions. The British National Gallery loaned its most renowned Moroni painting, The Tailor, for display at the Accademia Carrara in Bergamo, Italy in 2016. With all this recent attention, Moroni's altarpieces in local churches have been lovingly cleaned, text has been updated and augmented, and lighting improved to encourage cultural tourism. Albino now has a logo — the silhouette of a beautiful full-length Moroni portrait, the so-called Cavaliere in Nero, acquired in 2004 by the Museo Poldi Pezzoli, Milan. Ironically that celebrated painting was never in Albino!

The United States has not embraced Moroni's work as it has been in Italy and England, but not for lack of fine examples.2 In this article I will focus on four of Moroni's finest paintings in American museums. My selection is not art historically based, nor have I selected them with a particular theme in mind. The choices are personal, in that they represent, to me, Moroni‘s most intriguing and characteristic works. Two are relatively early, and two are from the final years of his career. 2

There has been one exhibition of Moroni’s work: Giovanni Battista Moroni, Renaissance Portraitist, curated by Peter Humfrey at the Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, in Spring 2000

Relatively little is known of Moroni's life. No one has been able to establish his date of birth. Baptismal records have not been found. General consensus and logic puts his birth year somewhere between 1520 and 1525. Even the date of his death, which had been established as February 1578, has been discovered to be incorrect based on evidence brought to light by Simone Facchinetti in his catalogue for a 2004-2005 exhibition, Giovan Battista Moroni: lo sguardo sulla realtà, 1560-1579, held at the Museo Adriano Bernareggi, in collaboration with three other Bergamese institutions. Lacking a definitive document attesting to Moroni's death, we know only that he was working on a commission, an adaptation of Michelangelo's Last Judgment, in 1579. This work still exists in its original site in the Church of San Pancrazio, Gorlago. By 1580, his student, Giovan Francesco Terzi, completed the painting.

The most significant facts that we do know are that Moroni was certainly from Albino, a small town outside of Bergamo, and that his father, Francesco, who was a master mason, apprenticed him to the renowned Brescian painter, Alessandro Bonvicino, better known as Moretto da Brescia . Apprenticed to Moretto in the sophisticated city of Brescia, Moroni would also become familiar with a significant school of painters, such as Romanino and Savoldo, both Brescian painters with whom Moretto had contact. Also, in Brescia, he would have seen Titian's Averoldi Altarpiece in the Church of Saints Nazaro and Celso. In his home province of Bergamo, Moroni would have seen the many works of Lorenzo Lotto , who had lived there, in this western-most outpost of the Venetian Terra Ferma, from 1513-1525. Lotto painted numerous altarpieces and portraits of Bergamese nobility, such as the Brembati and Suardi, the same families that Moroni later depicted.

Moroni learned to mimic his master's style to the point where scholars still have trouble distinguishing some very early religious works by Moroni from Moretto's. Moroni continued to rely on his master's compositions and prototypes well into his career, and for this reason, Moroni's large-scale religious paintings are often criticized for being uninventive and uninspired. One stylistic difference is that Moroni tended to use sharper, crisper forms and colors whereas Moretto's modeling is a softer sfumato that may have been Moretto's response to Da Vinci , who had spent time in nearby Milan.

Moretto brought Moroni as his apprentice to Trent, during the height of the Council of Trent (1545-1563). Trent, in these years, would have been a heady atmosphere for a young and impressionable artist. By 1548 Moroni was an independent master, taking up commissions from various religious institutions in Trent, which was experiencing a boom in art production following the new dictates regarding sacred and profane art issuing from the Council. Trent, in the Alto Adige, was an international center at the time, being a crossroad of Northern and Southern European culture, religion and philosophy. The Council of Trent was the epicenter of the Counter-Reformation, which had its eventual impact on the 17th century.

Moretto was primarily a painter of large-scale religious altarpieces, but he was also a master portraitist, and Moroni adapted ideas and compositional elements from Moretto in his earliest portraits. But Moroni developed a taste for portraiture, over the sacred works, which really accounts, in part, for Moroni's uniqueness.

199.8 x 116 cm (78 5/8 x 45 5/8 in.)

Charles H. and Mary F. S. Worcester Collection

1929.912

Art Institute of Chicago

201.9 x 116.8 cm (79 1/2 x 46 in.)

Timken Collection

1960.6.27

National Gallery, Washington, DC

The young painter was commissioned to paint full-length portraits of the Madruzzo brothers, nephews of the Prince-Bishop of Trent, Cardinal Cristoforo Madruzzo, who presided over the Council. Titian had painted Cristoforo's full-length portrait in 1552 (now in the Sao Paolo Museum of Art, Brazil). The Cardinal's nephews' portraits were probably executed shortly after by Moroni. Gian Lodovico's portrait is now in the Art Institute of Chicago and Gian Federico's portrait hangs in the National Gallery, Washington, DC. Very likely, the elderly Titian would have known these portraits, if not by an actual encounter, then, at least, by reputation. Moroni was already an independent artist, with a distinct vision placing each man in a defined, shallow space, with only vestigial swaggered drapes, accompanied by, in one, a lapdog, and in the other, a hound. The wall behind each is a neutral foil of light gray, with architectural elements that provide compositional stability via a play of horizontals and verticals. The figures have sharp contours, in keeping with Mannerist tendencies, but they lack the usual Mannerist elongations and enhancements. Moroni seems to have responded to the northern feeling for realism that he would have become familiar with in Trent during the late 1540s and early 50s. Moroni had an egalitarian eye, which looked upon the sitter and his clothing with equal interest. This equality of interest contrasts with Titian's rich color harmonies of reds, blacks and pinks. Titian places his black-clad subject in front of a massive crimson drape, which Cardinal Cristoforo pulls back to reveal a clock and documents on a writing table, references to his activities as head of the great church council. Where Titian generalizes, focusing attention on face and hands, Moroni particularizes, so we have a cool sense of who these young men are, and how expensively dressed. The sheen, color and weight of fabrics are as carefully depicted as the features of the sitter

Oil on canvas, 35.5 x 25 in. (90.2 x 63.5 cm)

Museum purchase

1912.60

Worcester Art Museum

Contemporaneous with these two portraits is the portrait by Moroni of an unknown young man that is now in the Worcester Art Museum, MA. The subject remains unidentified, but like many of Moroni's sitters, he has a nickname, the Bergamask Captain. Mina Gregori, the great scholar of Moroni, pointed out in her catalogue raisonné of 1979, that the man is not dressed as a soldier at all, but his left hand on the hilt of a sword suggested a martial air that stuck with the picture, despite the fact that a sword and dagger were a gentleman's accoutrements of the era, to be found in many sixteenth century male portraits. What's so striking about this painting is how Moroni has positioned the figure asymmetrically in the space. The slight diagonal axis of his body gives a sense of dynamism. It is as if he is passing a window frame and we are seeing him in an instant as he returns our glance. Adding to this impression are the simple geometries of a stone window casement that terminates before we glimpse the view outside and a diagonal shaft of light from the upper right corner of the painting. The line created by that shaft of light and its shadow seems to impel the movement of the man, while the casement creates a full stop within the narrow pictorial space. It strikes us as a strangely modern conception, a quality remarked upon in much of the literature about the painting. There's evidence that the bottom of this painting was cropped at some point in its history, and that the lower part of the painting probably extended, perhaps to a full-length figure (there's no extant image of how it originally appeared). Even if we imagine this figure entirely, it's hard to see the painting as a typical sixteenth century product. The man looks oddly contemporary. We could easily imagine him in modern clothing. We have the uncanny feeling that he is seeing us, as much as we are seeing him. Moroni has created a crisp, dark silhouette against a light, neutral background. Diagonals of forearm, dagger and sword complement the larger diagonals to render a living presence in motion. The sense of palpable flesh in the face and hands, and masterful attention to hair, whiskers and of the body within the clothes, all add up to this presence.

In fact it was this painting that made me notice Moroni about 44 years ago, when I first saw it at the Worcester Art Museum. At the time I thought, who is this Moroni, and why had I never heard of him before? I couldn't find any monographs or extensive articles about him in English. My curiosity impelled me to do further research. I found old books, in German and Italian (neither of which could I read at the time) that at least gave me some impression of Moroni's achievements. I did find a thin, large format book by Emma Spina, part of the I Maestri del Colore series, published by Fratelli Fabbri Editori in 1966, which I bought at the old Rizzoli Bookshop on Fifth Avenue. The black and white and few color plates confirmed that what I saw in the Worcester painting wasn't exceptional, but characteristic of his work. Then I discovered the two pictures, side by side on display in the Metropolitan Museum, Bartolomeo Bonghi and Abbess Lucrezia Agliardi Vertova.

Why had I not noticed them before?

This very fine painting was cleaned in 1991, when the decision was made to remove posthumous additions of a family coat of arms on the upper right, and a memorial inscription on the left, just below the window. The cleaning brought back Moroni's original composition, which includes a beveled windowsill, providing a generous, luminous truncated trapezoid, slightly cut off at the corner by the sitter's right arm. It also brought back the cooler palette, hidden behind a coat of yellowed varnish. The figure was now free of the awkward crowding created by these later additions.

Oil on canvas, 36 x 27 in. (91.4 x 68.6 cm)

Theodore M. Davis Collection, Bequest of Theodore M. Davis, 1915

30.95.255

Metropolitan Museum of Art

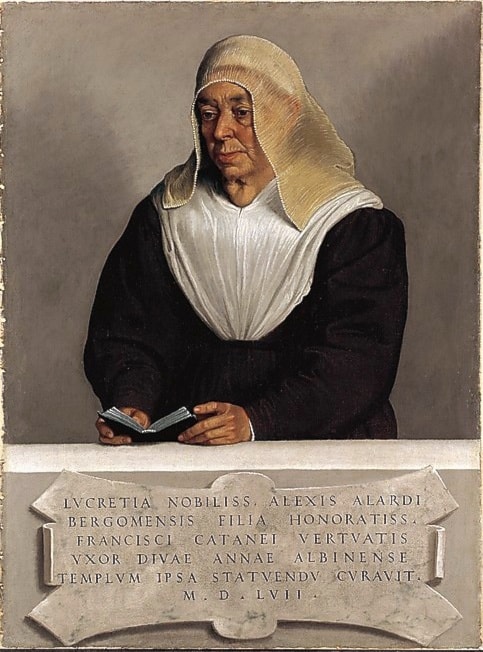

The painting that most struck me, and strikes me still to this day, is Moroni's portrait of Abbess Lucrezia Agliardi Vertova. This work has a stark simplicity. The elderly sitter stands or sits behind a stone ledge, one-third up from the bottom of the canvas. The fictive stone entablature has a Latin inscription on a veined marble escutcheon that tells us the sitter was "Lucretia, daughter of the most noble Alessio Agliardi of Bergamo, wife of the most honorable Francesco Cataneo Vertova, herself founded the Church of Saint Anne at Albino. 1557." Such inscriptions are not uncommon in Moroni's work, although this one is the most complex.

Lucrezia is isolated against one of Moroni's gray walls, subtly modulated from middle gray at the bottom, to light gray at the top. Another shaft of light from the upper right corner divides the wall, and creates a diagonal that cuts across the square space that the figure occupies. Her shadow, cast on the opposite side of the wall, answers this diagonal, amplifying her solidity in a credible space. She wears a dark maroon dress, with a wide white overblouse. The only additional touch of color is in the blue-green page edges of the small prayer book she holds in her hands, resting on top of the stone ledge.

A diaphanous ivory veil frames her face, revealing the side of her face and the white cap underneath. Unlike the Bonghi and Worcester portraits, her gaze doesn't meet the viewer's eyes. This might have indicated the modesty of the sitter, and is somewhat exceptional to Moroni's other female portraits, whose gazes usually do greet the viewer's, as in most of his male portraits. The face we see is empathetically recorded, goiter and all, with no attempt at flattery. Like some Roman verist portrait bust, Moroni took pains to describe Lucrezia's aging flesh. We read these features as candor on the artist's part, shared by the sitter. In fact, we always feel the complicity of the sitter in Moroni's paintings, which adds to their sense of modernity.

The painting seems so modest and understated that we can miss the virtuosity of its facture: the subtle modulations of gray, white and ivory, the gorgeously painted, fine pleats of the veil, and the crepey flesh of the neck. Moroni's attention to details lies somewhere between the intense, hair-by-hair details of the Flemish and the painterly elisions of the Venetians. Recent scholars of Moroni believe that he was also responding to the policies on "profane" art set during the Council of Trent that had recommended that portraits reflect the true appearances of sitters, warts and all. In fact, Moroni frequently included facial tumors and asymmetries in many of his portraits.

16.52 x 14.88 in.

Gift of Samuel H. Kress Foundation

1961.013.023

University of Arizona Museum of Art

In the third of my small selection, the so-called Portrait of a Magistrate in the University of Arizona Museum of Art, Tucson, there is a decided downward turn to the proper left side of the mouth. This feature might indicate that the sitter suffered a slight stroke. It certainly adds to the impassive stare of the sitter. The format is much more modest, and the color range is at once warmer and narrower. The dark background isolates the tightly cropped figure in an ambiguous space, similar to that used in Tintoretto's portraits.

Approximately thirteen years separate this painting from the portrait of Lucrezia Agliardi Vertova. It is one of many small bust-lengths that Moroni painted during his years back in Albino. These portraits, frequently of unidentified men and women, show the local petty nobility and tradesmen. We don't know in fact if this man was a magistrate. His baretto and soft white collar don't really tell us what he did for a living. Most of Moroni's male sitters wear black, which indicates a certain level of prosperity since black was an expensive dye. The aged man seems to look upon us with an appraising gaze, one brow slightly raised. Once again we feel that we're in the presence of a living being.

Moroni was a thin painter, by that I mean, he worked with thin but opaque paint. In earlier works, it was his practice to blend lights into intermediate tones by fine zig-zags of paint, unlike Moretto's seamless sfumato. In his later work, this tendency disappears but he still builds form with tonal areas rather than smooth, imperceptible transitions of tone. In his later works, his modeling seems more related to Venetian techniques, but stops short of Titian's complex use of glazes, impasto and impressionistic handling. We must bear in mind too, that Moroni was only in his fifties when he died, so he never developed a really "late style" the way Titian did in his seventies to nineties. Using some signed and dated works and costume as guides, we can locate the works of the last years of the 1560s-70s, and see that his palette warms somewhat although still favoring a limited range of colors. The silvery palette reappears in certain pictures in which he uses architectural settings. The late full-lengths in Milan, Boston and Bergamo show this palette again, but with an almost Velazquez-like painterliness.

20 x 161/2 in (50.8 x 41.9 cm)

The Norton Simon Foundation

F.1969.29.P © The Norton Simon Foundation

Perhaps the ultimate expression of Moroni's final style in an American museum is the Portrait of an Elderly Man in the Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, CA. This most tenebrous image seems to hover from the gloom, the face is dramatically lit while the upper body seems entirely unilluminated. This might be partially due to darkening of pigments whereas the lead white mixed into the flesh tints has remained bright. It seems that Moroni has followed every crevice in the face by building small clots and squiggles of paint to represent shadows and highlights. At some point, a collector probably added a strip of canvas to the top, to give the head some more breathing room, as Moroni tended to crop closely to the top and sides of figures. This "improvement" has been found in a number of Moroni's paintings and was remarked upon by Allan Braham in his catalogue for a 1978 exhibition at London's National Gallery celebrating the 400th anniversary of Moroni's death.3 In fact the National Gallery has a portrait of a somewhat younger man, wearing sleeves of maille, with such strikingly similar features that he could be the sitter's younger brother (like the Pasadena portrait it's dated to the 1570s), and like our portrait, it has an inch-wide strip added to the top. As Moroni frequently painted family members, the London sitter very likely was a close relative. Somehow the expression of the London sitter, despite the almost identical three-quarter view of the head and raised right brow, seems sardonic rather than piercing as is the gaze of the older man in Pasadena. 3

Giovanni Battista Moroni, 400th Anniversary Exhibition, Allan Braham, p. 18, The National Gallery, London, 1978.

Moroni's realism seems to anticipate Velazquez more than any other Baroque painter. We know that Van Dyck saw Moroni's painting, misattributed to Titian, at the Farnese Palace in Rome. That painting, the so-called Titian's Schoolmaster, is now in the National Gallery, Washington and Van Dyck's sketch still exists. It's not at all unlikely that Velazquez would have seen portraits by Moroni in Venice and Rome during his two trips to Italy. Angelika Kauffmann owned a Moroni portrait. Mary Cassatt urged her old master collector friend, James Stillman, to buy Moroni's portraits of the Madruzzo brothers from a Parisian dealer who offered all three of the Madruzzo portriats. In Cassatt's own words, "Opposite [the Titian] hung two most superb portraits full length by Moroni...now in my opinion, but I saw the pictures only by electric light, these two are more interesting than the Titian."

So what is it that makes Moroni's people so real, so present? In their reviews of a small exhibition of paintings from the Accademia Carrara at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2012 , both Sanford Schwartz and John Yau remarked on the potency and freshness of Moroni's realism. They invoked his ability to make us feel as if we can meet his sitters face to face, today, without filters of style or sense of remoteness of time.

- Robert Bunkin, November 24, 2017

- 1

-

Works by Moroni are found in the Cleveland Museum, The De Young Museum, San Francisco, Isabella Stewart Gardner and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, VA. Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Princeton Art Museum, Detroit Institute, Brooks Museum of Art, Memphis, Minneapolis Museum of Art, Ringling Museum, Sarasota. There are several attributed works in other museums, as well as at least one portrait in private hands.

- 2

-

There has been one exhibition of Moroni’s work: Giovanni Battista Moroni, Renaissance Portraitist, curated by Peter Humfrey at the Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, in Spring 2000

- 3

-

Giovanni Battista Moroni, 400th Anniversary Exhibition, Allan Braham, p. 18, The National Gallery, London, 1978.